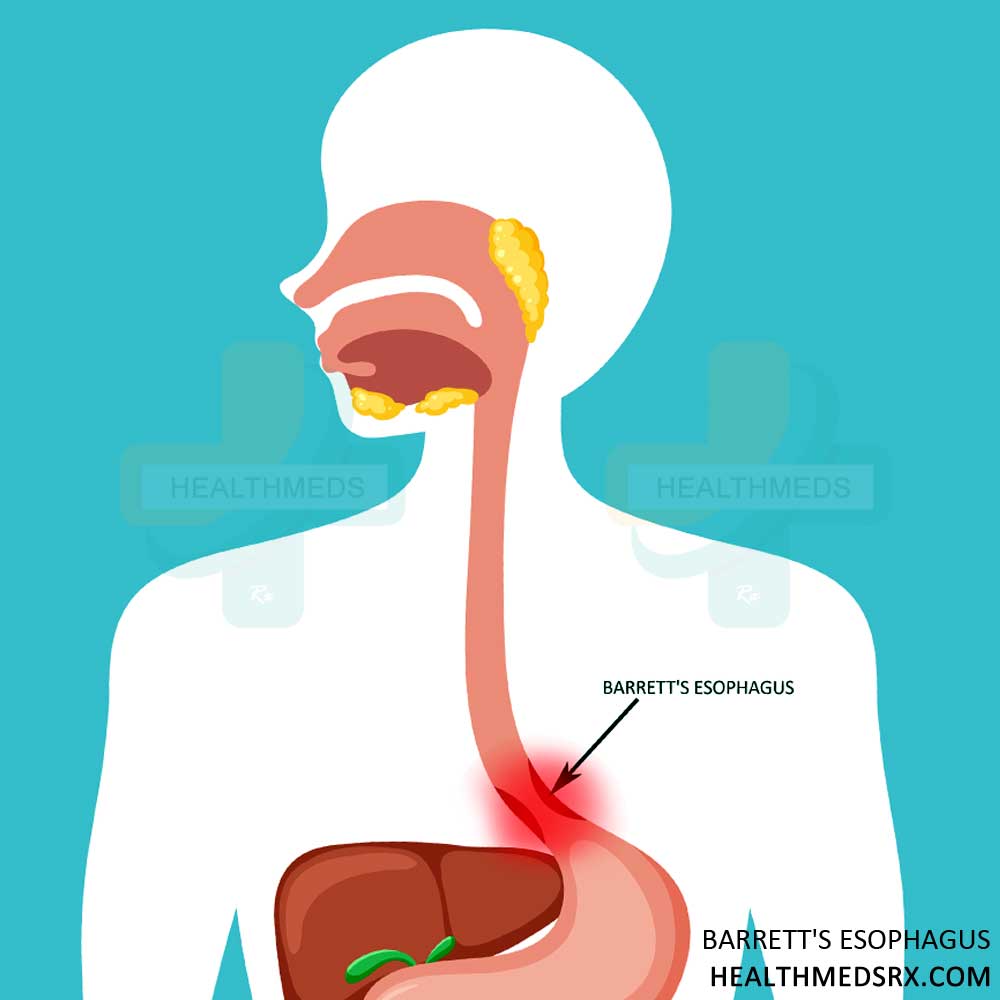

Barrett’s esophagus is a disorder caused by exposure to stomach acid that damages the tissue lining the lower esophagus (the muscular tube that connects the throat to the stomach). The most common cause of this is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), where the stomach acid repeatedly backs up into the esophagus.

Over time, acid reflux can lead to the replacement of normal esophageal cells with abnormal ones. Although these abnormal cells are more resistant to stomach acid, they are still prone to turning into cancer cells. Specifically, the inner mucosal layer undergoes a transformation from squamous epithelial cells to column-shaped cells resembling those found in the intestines. This abnormal intestinal-like tissue is called Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition that affects many individuals, yet understanding and managing it can be complex. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the intricacies of Barrett’s esophagus, exploring its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options. Whether you have been recently diagnosed or are seeking to deepen your knowledge of this condition, this guide will provide you with valuable insights and practical strategies to effectively manage Barrett’s esophagus.

Causes and Risk Factors

The main cause is chronic acid reflux disease, also called gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In GERD, stomach acid frequently flows back up into the esophagus, causing inflammation or damage to the esophageal lining. As a result, normal cells in the esophagus can change over time and develop into precancerous cells, ultimately leading to Barrett’s esophagus.

Additional key risk factors include

- Age: Barrett’s esophagus can occur at any age, although it is more common in middle-aged and older adults. This condition is rare in children.

- Sex: Men are twice as likely to develop it than women. On the other hand, esophageal adenocarcinoma occurs more often in women than in men.

- Race: White people are more likely to develop Barrett’s esophagus than black, Asian, or Hispanic people.

- Obesity: Being overweight increases the risk by increasing acid reflux and abdominal pressure.

- Smoking: Chemicals in smoke can damage the lining of the esophagus and increase the risk of cancer.

- Alcohol: Regular drinking can relax the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing acid and stomach contents to back up into the esophagus.

- Hiatal hernia: This common condition can worsen acid reflux by weakening the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

Symptoms of Barrett’s Esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus often produces no noticeable symptoms. Some people may experience

- Chronic heartburn

- Difficulty swallowing

- Chest pain

- Gastrointestinal issues

Barrett’s esophagus does not always show these symptoms, as it is also frequently seen in many other disorders, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The tissue changes characteristic of Barrett’s esophagus usually do not hurt or cause discomfort. As a result, many people don’t know they have the disease until a screening or endoscopy for other reasons reveals it.

The lack of symptoms can be dangerous because untreated Barrett’s esophagus can progress to esophageal cancer. That’s why screening can be extremely important for individuals who are at a high risk of developing certain health conditions. Diagnosing it early allows for monitoring and treatment before the cancer develops.

Diagnosing Barrett’s Esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed through an endoscopy procedure that involves using a flexible tube with a camera to examine the esophagus and take tissue samples for biopsy. These samples are essential to accurately diagnose and confirm the biopsy results of Barrett’s esophagus. In addition to endoscopy and biopsy, it can also be diagnosed with imaging tests such as an upper GI series or imaging scan. These tests and procedures are necessary to diagnose the disease and monitor it to ensure proper care and therapy.

Screening for Barrett’s Esophagus

If you suffer from frequent heartburn or acid reflux, it’s important to talk to your doctor about being screened for Barrett’s esophagus. In general, you are advised to be screened for:

- Frequent acid reflux or heartburn. Frequency is considered if you have symptoms at least twice a week.

- Heartburn for many years. The longer you experience reflux symptoms, the higher your risk.

- Heartburn that worsens over time or becomes uncontrollable after taking the medicine.

- Family history of Barrett’s esophagus. Those family members who have Barrett’s are at higher risk.

- Additional risk factors, such as smoking, being older than 50, being overweight, and caucasian race. The more risk factors, the higher the chance.

Treatment Options for Barrett’s Esophagus

The main goals of treating Barrett’s esophagus are to manage GERD symptoms, monitor the condition, and adopt lifestyle changes to reduce irritation of the esophagus.

- Medications to control GERD: Proton pump inhibitors, such as lansoprazole or omeprazole, are usually recommended to reduce the production of stomach acid. This reduces future esophageal damage and helps manage GERD symptoms.

- Monitoring: Patients need regular endoscopy, to monitor cells and look for signs of dysplasia or cancer. Recurrence varies according to biopsy results but is usually every three to five years.

- Lifestyle changes: Losing weight if overweight, avoiding alcohol and smoking, eating fewer meals, and delaying bedtime after meals can all help reduce GERD and esophageal inflammation.

- Surgery in some cases: Surgery may be necessary in certain situations to remove abnormal cells and tighten the lower esophageal sphincter to prevent reflux in people who do not respond well to medications or who develop precancerous or cancerous changes. Most people do not require a major surgery, as it is not necessary in their case.

Risks and Complications Associated with Untreated Barrett’s Esophagus

If left untreated, Barrett’s esophagus can lead to complications, such as erosive esophagitis, which is an inflammatory disease that damages the lining of the esophagus. Patients with Barrett’s esophagitis are also more likely to develop esophageal adenocarcinoma (a type of cancer).

The estimated risk of esophageal cancer for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is 0.12% to 0.33% per patient-year. This means that within a year, someone with Barrett’s esophagus has a 0.12 to 0.33% chance of developing esophageal cancer. Over 10 years, the risk ranges from 2-3%.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma is an aggressive cancer with a poor survival rate. However, early detection of cancer increases the chances of successful treatment. Therefore, for patients with Barrett’s esophagus, screening endoscopy is essential for early detection of dysplasia or cancer.

Another possible complication is stricture development or narrowing of the esophagus. This happens when inflammation and abnormal cell growth cause scar tissue to form and the lining of the esophagus to tighten. Strictures can lead to challenges and discomfort while swallowing. Strictures of the esophagus can be treated by using an endoscope to stretch or dilate it.

Coping and Living with Barrett’s Esophagus

Managing Barrett’s esophagus can be challenging, but lifestyle tips and support strategies can help. Stress management, a healthy diet and avoiding trigger foods can help reduce symptoms. It is crucial to follow the treatment plans prescribed by healthcare providers and attend regular check-ups to monitor the condition. Individuals with Barrett’s esophagus can benefit from seeking support from healthcare professionals, support groups, or counsellors to cope with the condition. Remember that you are not alone, and there are resources available to help you navigate life with this condition.